The making of 'showman' Duplantis - and how high can he go?

Todd Lane - track and field coach at Louisiana State University

Kate Rooney - British Olympic pole vaulter

Johanna Duplantis - Mondo's younger sister

Scott Simpson - coach of British pole vaulter Molly Caudery

For three decades, the men’s pole vault was dominated by two names.

Sergey Bubka

Renaud Lavillenie

In 1984, Ukraine’s Sergey Bubka set a world record of 5.85m. It was the first of 17 times he would set a new global mark.

Frenchman Renaud Lavillenie ended his dominance in 2014, taking the record to 6.16m.

But there was a new kid on the blocks - or, should we say, the runway.

In February 2020, a 20-year-old Armand Duplantis - ‘Mondo’ as he’s more commonly known - broke Lavillenie’s record by one centimetre.

The new mark was 6.17m. But not for long.

Less than a week later, Duplantis went over 6.18m. For the five years since, the Swede has continued to nudge up the bar in one-centimetre increments.

On average, he breaks the world record three times per calendar year.

A clearance of 6.29m at the Hungarian Grand Prix in August 2025 meant he broke the record for the 13th time.

The closest anyone has come to challenging Duplantis this season was when Emmanouil Karalis cleared 6.08m in August 2025.

So Duplantis is more than 20 centimetres ahead of the rest - and will fancy himself to set a new world record of 6.30m at the World Athletics Championships in Tokyo.

“He’s probably vaulted more hours than anybody else in the world.”

Todd Lane is a track and field coach at Louisiana State University (LSU), where Duplantis spent a year before leaving to turn professional.

Lane got to know Duplantis when he coached his brother Andreas, who was also a pole vaulter for LSU.

“One of the things that makes Mondo so good is that he’s a coach of himself,” he says. “Mondo always had insight into Andreas’ vaulting.

“He understands the event very, very well.”

It helped having a pole-vault pit in the back yard of their home in Louisiana, where Duplantis grew up alongside his two brothers and younger sister Johanna, who is also a professional pole vaulter.

“My brothers and I would jump in the back yard - it was our playground,” says Johanna.

“Our dad introduced us to the pole vault. We just fell in love with it - a kind of domino effect.”

Greg Duplantis is a former elite pole vaulter. He and wife Helena - a Swedish former heptathlete and volleyball player - coach their son, who competes for Sweden.

“One memory is just jumping in the back yard after school and Mondo would coach me,” says Johanna.

“There’s this video of him coaching me, and he was just like: ‘That was terrible!’ I was literally in my school uniform!

“There’s a lot of memories in that back yard that I will cherish forever.”

Those hours practising in the back yard soon brought results.

Mondo holds multiple international age-group records:

AGE | NAME | HEIGHT |

7 | Armand Duplantis | 2.33 |

8 | Armand Duplantis | 2.89 |

9 | Armand Duplantis | 3.20 |

10 | Armand Duplantis | 3.86 |

11 | Armand Duplantis | 3.91 |

12 | Armand Duplantis | 3.97 |

17 | Armand Duplantis | 5.90 |

18 | Armand Duplantis | 6.05 |

19 | Armand Duplantis | 6.05 |

Lane recalls people at athletics meets saying: “We’re only here to watch Mondo.”

“All the running events were done, and people stayed in the stands," he says.

In the years since, Duplantis' fanbase has grown far beyond Louisiana.

He has almost two million followers across TikTok and Instagram, and between breaking world records he has been recording music. His debut single Bop came out in February and has had more than two million streams on Spotify.

So is the Duplantis we see on our screens different to the one off camera?

“No,” says Johanna. “He is very confident and humble. What he puts out there is who he is.”

“He might be humble but he is also a great showman,” says Lane - pointing to Duplantis setting his ninth world record at the Paris Olympics as an example.

“Whether it’s the Rolling Stones opening up at Wembley, or whatever, he lived up to the greatest performance you could.

“What he did in Paris was like he should be on Broadway doing plays.”

Johanna says her brother has always had it “pretty much perfect”.

But what does pole-vault perfection look like?

Helen Bayne is a senior movement scientist at the Western Australian Institute of Sport, and works with some of the best vaulters in the world to improve their performance.

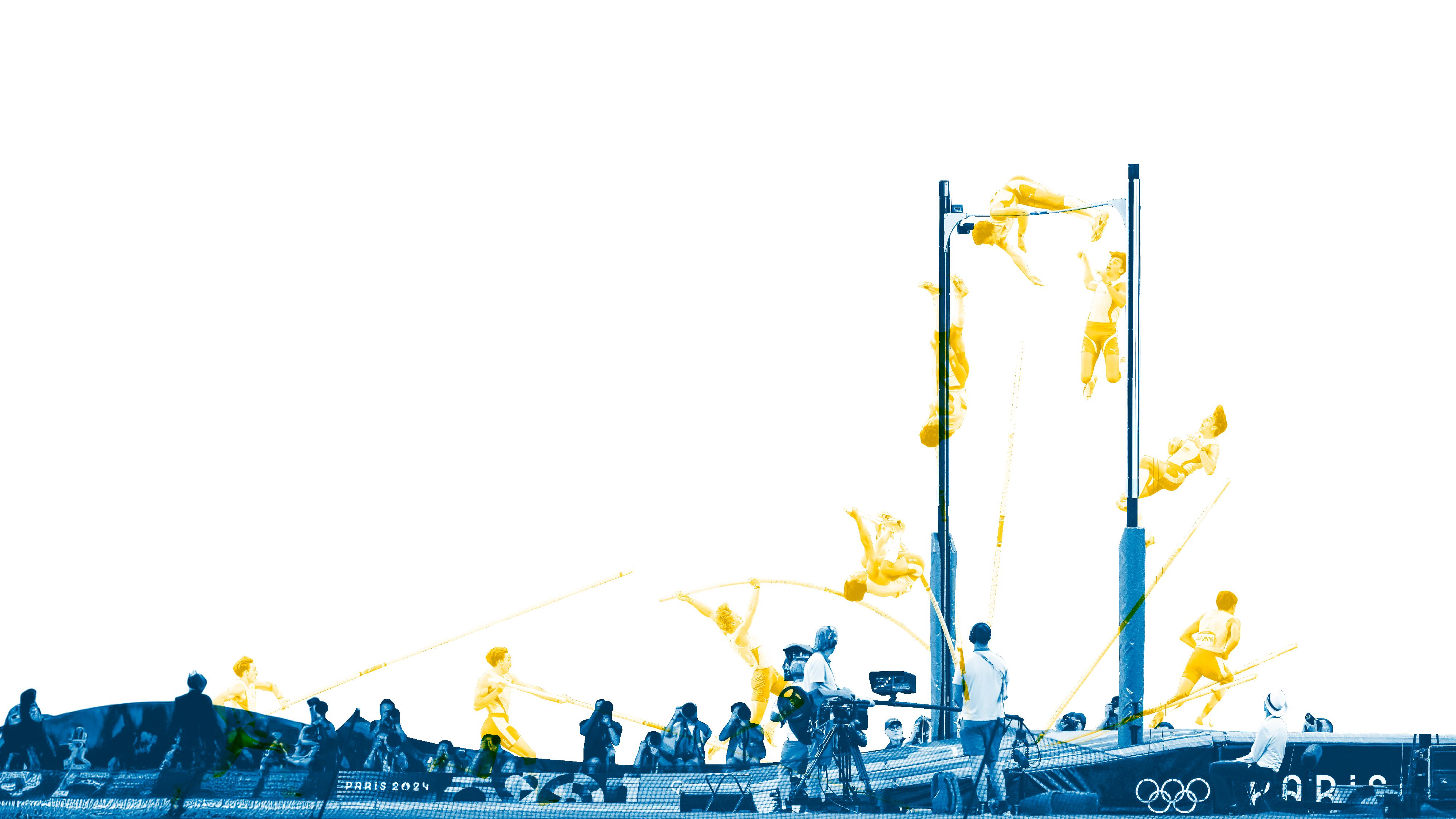

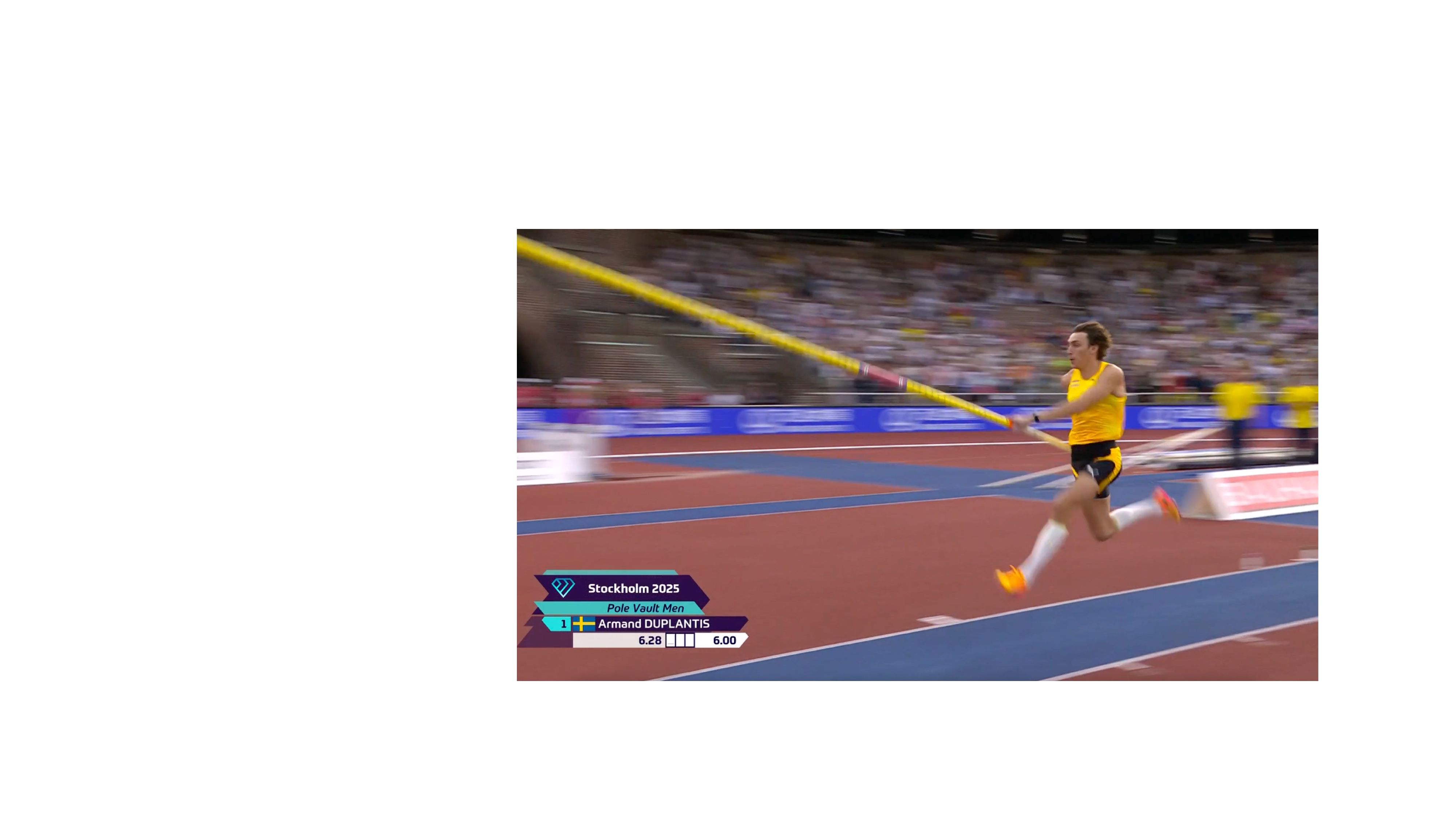

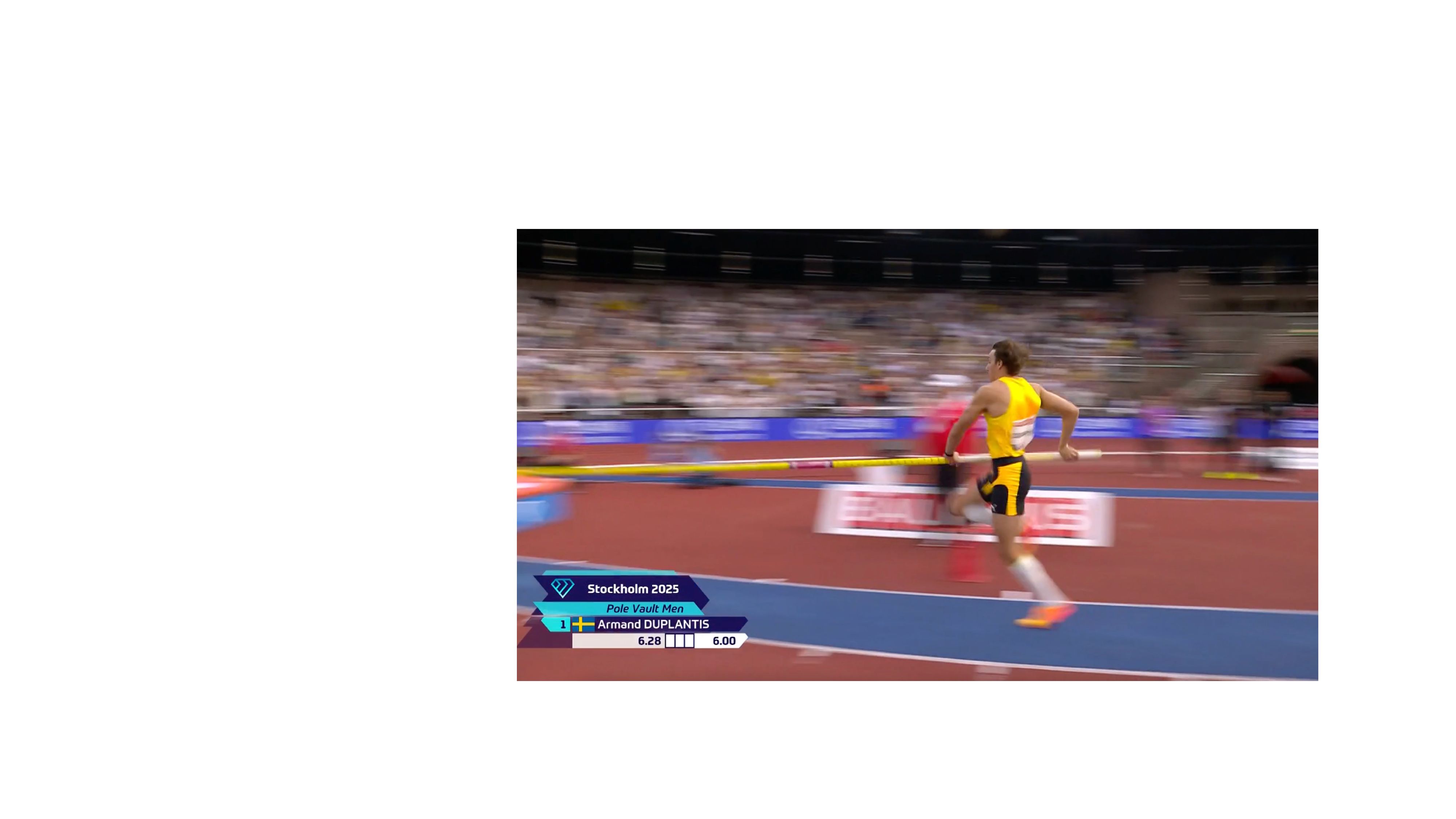

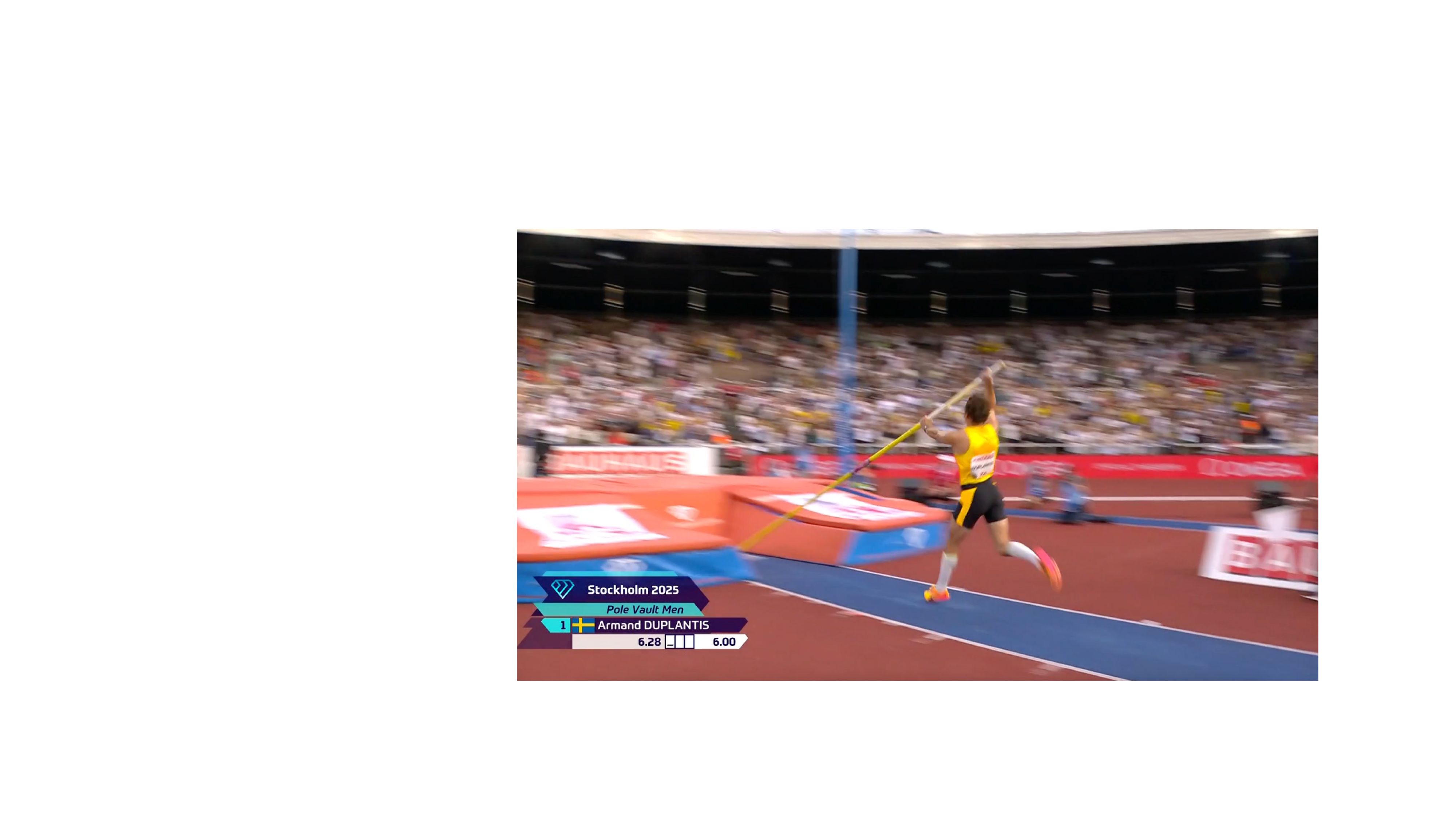

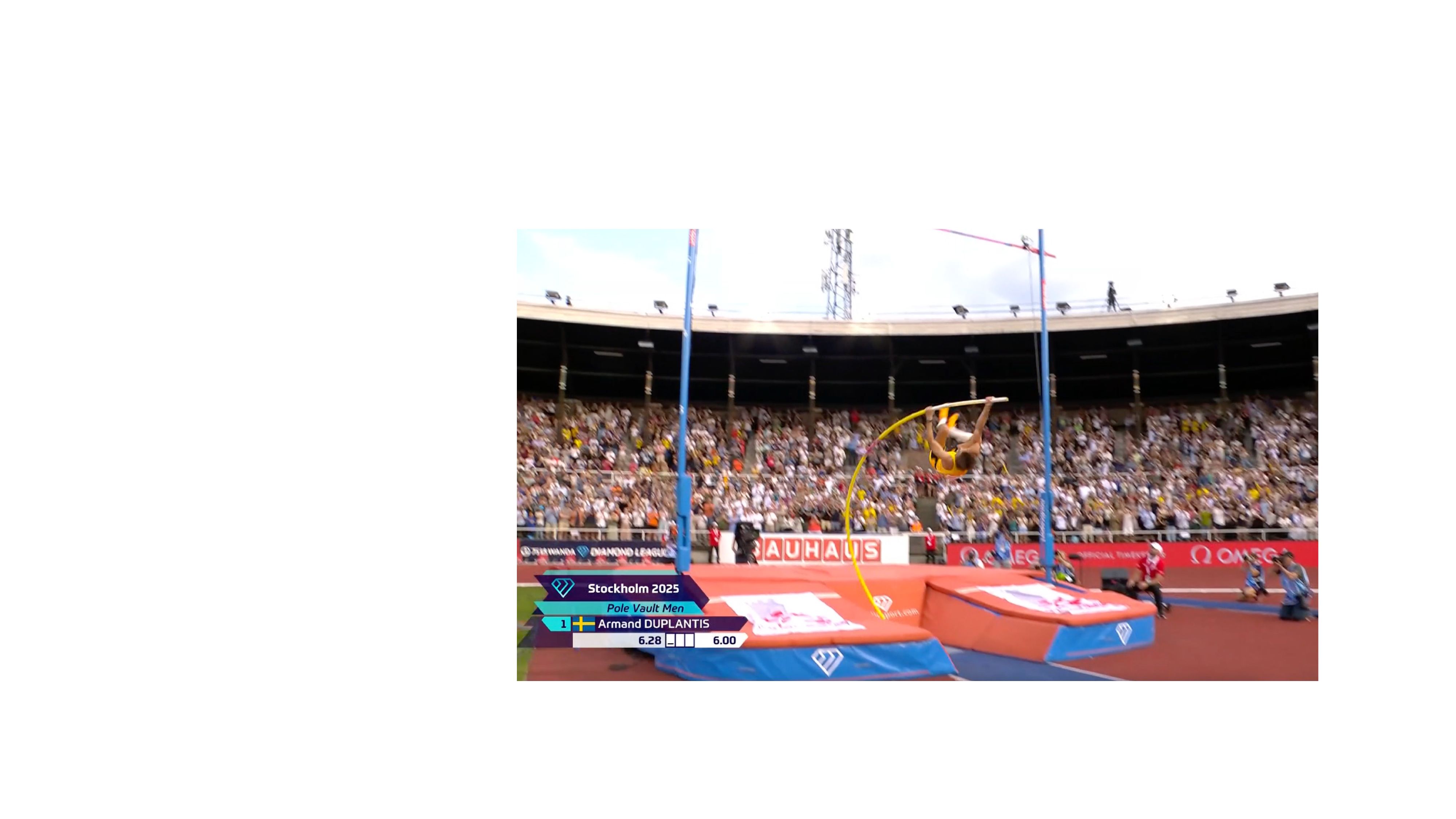

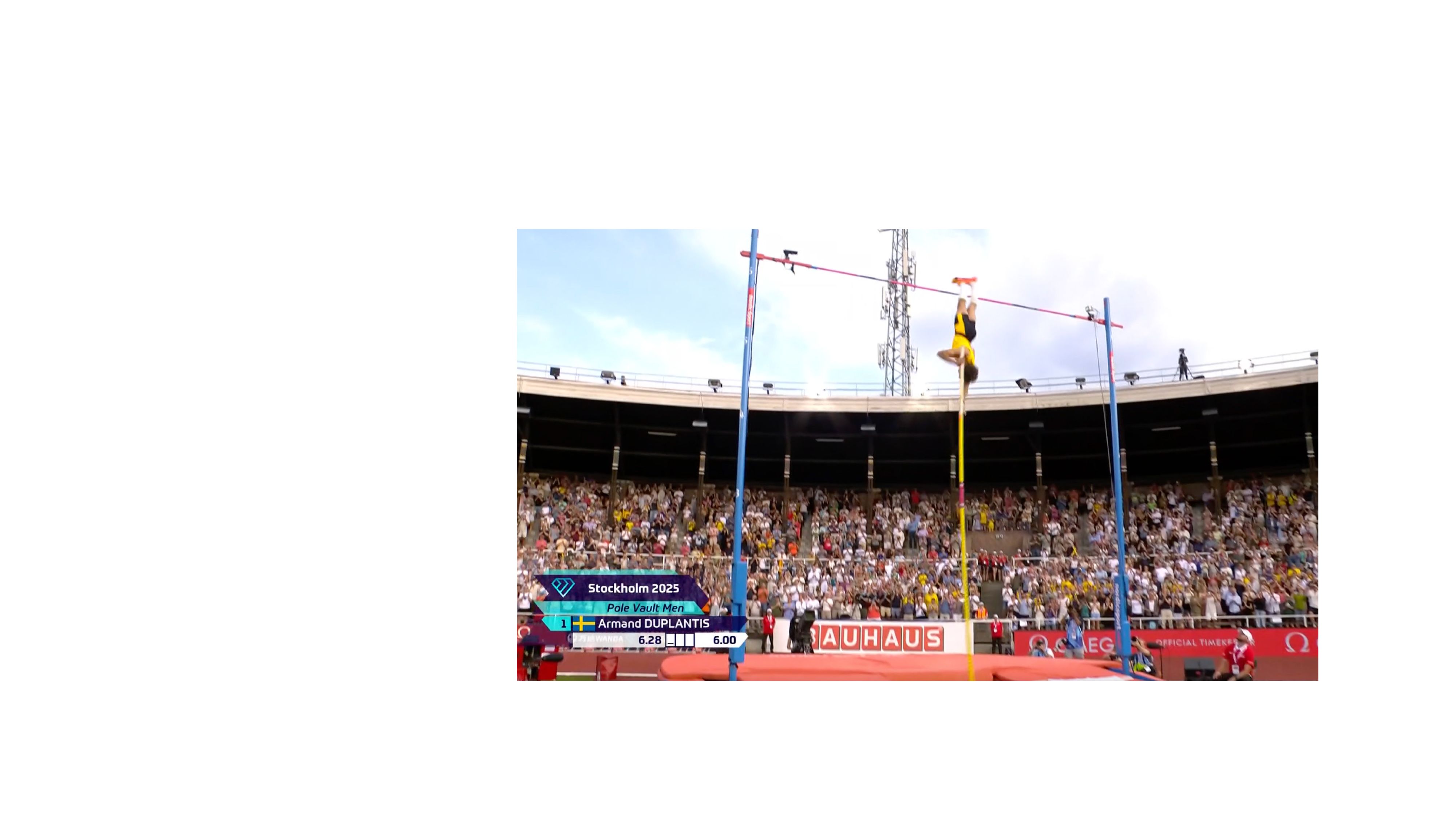

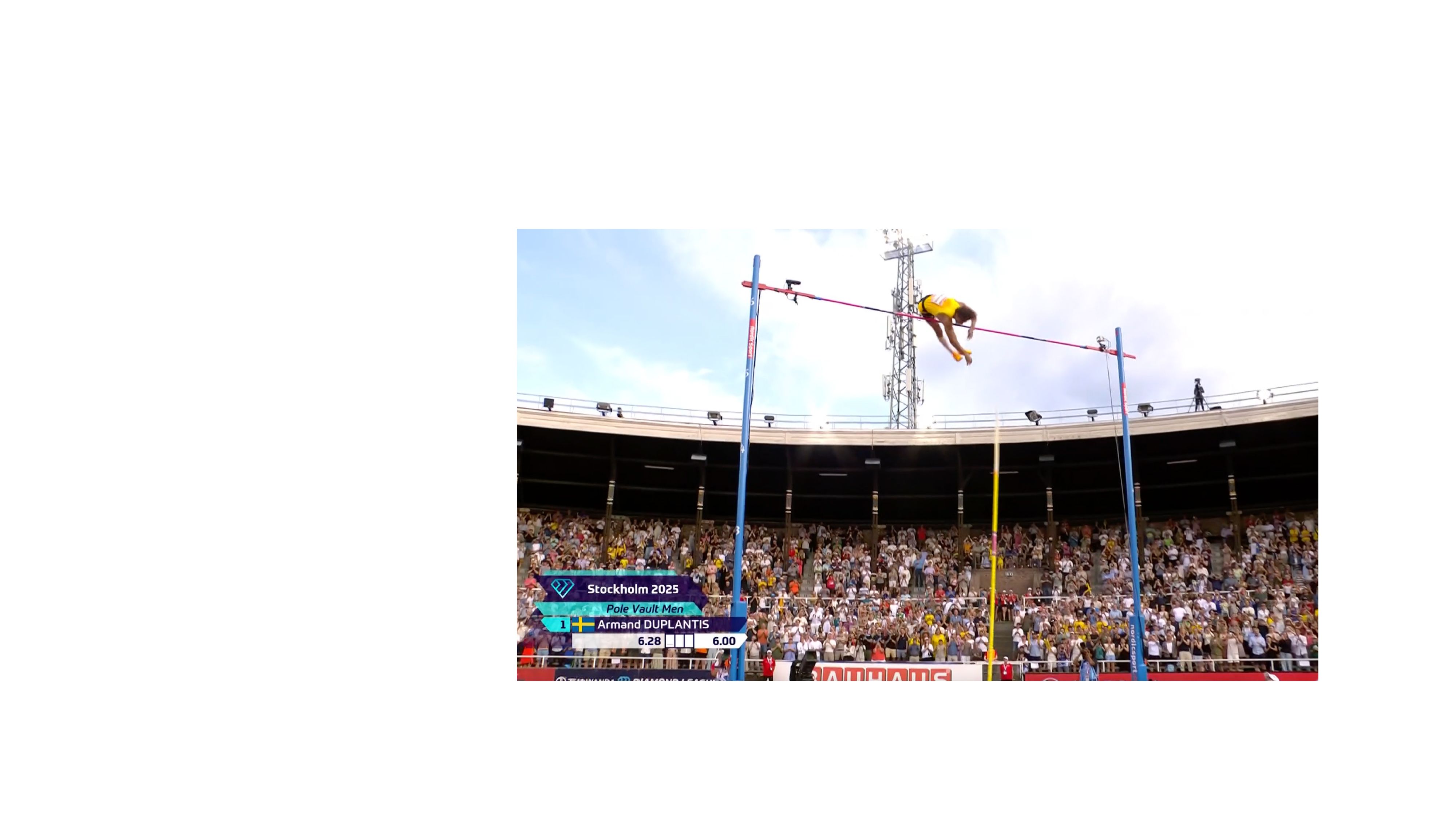

The images that follow are from when Duplantis set the world record for the 12th time by clearing 6.28m at the Stockholm Diamond League in June 2025.

This is the key thing that differentiates Duplantis from other elite pole vaulters.

The key task in pole vault is producing energy. The faster athletes move, the greater kinetic energy they produce.

Duplantis takes 20 steps down the runway and can reach 10.3 metres per second at the point of take-off.

By comparison, other male pole vaulters might hit 9.4-9.7m/s.

Moving a pole that is five metres or longer from an upright position to the ground helps the body move forward quickly.

But it’s a challenge.

You don’t just drop the pole down in front of you, you do it in a controlled way that is timed perfectly.

Get that right, and athletes are in the ideal position for take-off.

Most vaulters will land the end of the pole directly in the plant box.

But Duplantis places it down just before, and lets the pole slide along the runway before it hits the groove at the back.

This could allow him to maintain his velocity over the last couple of steps.

Duplantis’ take-off position is what is called ‘close’ or ‘under’.

When he launches from the ground, his foot is about 20-30cm in front of his hand.

This allows him to capitalise on the speed he generates in the run-up, transferring some of this energy to the pole as he starts to bend it before he leaves the ground.

Getting this right is essential.

Too close and you lose the space you need to take off properly; too far and it’s harder to apply the necessary force to the pole.

Once in the air, the vaulter pushes the pole upwards and forwards while at full stretch.

Duplantis swings his bottom leg through and tucks into a small ball, staying behind the pole.

At this phase of the vault, there are two energy systems - the pole and the athlete.

Duplantis' rotation adds energy as the pole bends. The best vaulters can use this to add energy to the overall process.

When the pole starts to straighten, Duplantis is fully upside down and rotates his body to face away from the runway while still applying pressure to the pole.

Duplantis’ pole is 5.2 metres long. His top hand grips it 10-20cm below that.

So when the bar is set to the 6.28m he jumped in Stockholm, there is well over a metre from the highest point of contact on the pole and the bar he is trying to clear.

All of the energy generated by the time the vaulter releases the pole needs to leave them with enough vertical velocity to keep moving upwards - high enough to clear the bar.

The world records in the high, triple and long jump were all set in the 1990s, and remain unbroken.

Pole vault is different.

The men’s world record has been broken 14 times since 1994 - 13 by Duplantis.

“The men’s long jump record is outrageously long,” Olympic pole vault bronze medallist Holly Bradshaw told BBC Radio 5 Live. “Mike Powell can put that jump out there and was like, ‘I’m never going to break that again’.

“In the pole vault, you can just go one centimetre at a time.”

Athletes receive bonuses of up to $100,000 (£74,000) for breaking world records at certain World Athletics meetings.

In addition, it is thought Puma - Duplantis’ sponsor - awards bonuses for breaking world records, though it was unwilling to disclose any contractual details.

“There’s been some competitions where Duplantis has jumped 6.10m, and then stopped and not attempted the world record,” said Bradshaw. “That to me says the meet has no bonus for a world record so, in his eyes, why would he break it?”

Duplantis’ strategy of breaking the world record centimetre by centimetre is not new. Since 1985, the men’s pole vault record has been broken by no more than two-centimetre increments each time.

“It’s incredibly sensible,” former British record holder Kate Rooney tells BBC Sport.

“If he had jumped 6.35m and then was jumping 6.10m all the time and couldn’t break it, you wouldn’t have that attraction.

“He has put pole vault on the map. He’s doing bits for athletics in general.”

“Mondo is super laid-back, very, very talented, and hard-working,” British pole vaulter Molly Caudery tells BBC Sport.

“Combine his pure speed and mindset, he is formidable,” adds Caudery’s coach Scott Simpson.

Pole vault is a discipline that relies on confidence and courage - things Duplantis is not short on.

“Tadej Pogacar in cycling, Kobe Bryant in basketball... if you look at the great athletes in the world, they have a mentality that is unshakeable,” says Lane.

Those around Duplantis believe his mindset is no different.

His sister Johanna says: “My three brothers were always competitive growing up, like at every little thing. It helped me become so competitive watching them.

“If he has something on his mind, he is going to do it. His mental strength is one of a kind.”

“There have been a few attempts to model this from a physics point of view," says Bayne. "A couple of those have pointed to a 6.50m mark.

“But there are also arguments that suggest this could be flawed, as mathematical calculations don’t always take into account the rest of the body parts that have to contort over the bar.”

Ultimately, the unknown of how far human limits can stretch is what keeps us hooked.

“I always said that I don’t think 6.40m is possible,” says Bradshaw. "But he defies the odds so I don’t think we can put a cap on it.”

What does Duplantis think?

When asked whether there is a limit to how far the bar can go, he told the BBC’s More Than Score podcast: “The next huge barrier would be 6.40m, so I think that all those are very possible and hopefully I’ll keep pushing past that.

“I don’t see the end any time soon, so I guess in that way I feel like it’s a bit limitless.”

Credits

Images by Getty Images

BBC